Alas, my only blog about Vertigo was cut cruelly short due to a sudden strike of inspiration. But fear not! For now all shall be revealed. Hopefully.

There has been a lot of focus, both in class and among prominent film critics, of Hitchcock’s use of color in Vertigo. However, I don’t think that any of these discussions have even come close to fully exploring the relationship between specific colors, the main characters, and general recurring themes. Furthermore (I shock myself with my own unadulterated audacity), they are all missing a key element in the spectrum (haha) of analytical possibilities. My claims will be ambitious, my theories convoluted, and my discussion tangential. Ready?

The color green is clearly a frequent narrative and thematic device in Vertigo. Madeleine/Judy seems represented by green fairly consistently throughout the film. In Scottie’s first glimpse of Madeleine in the restaurant, she is wearing a green wrap over a black dress, which highlights her in the crowded room, drawing his attention immediately to her and holding it. Similarly, Judy is wearing a green dress when Scottie spots her on the street in the second half of the film. And when she steps out of the bathroom after putting her hair up (transforming into Madeleine), she is bathed in a hazy green light, presumably issuing from the neon hotel sign through the window. But, as Dr. Campbell said, we know that’s really not it. And of course, Roger Ebert has to put his two cents worth in, stating that the green light is “apparently explained by the neon sign, but is in fact a dreamlike effect.” Sadly, Ebert leaves his discussion of green here. Good thing we have the editor’s notes. Jim Emerson, Ebert’s editor, knows better than to leave it at this. He explains,

the thing that imprinted itself indelibly on my brain, was something simple and powerful: the color green. Say “Vertigo” and I see green. For the color green is associated with Scottie Ferguson’s vertigo and, especially, its underlying cause: the dizzying fear of falling, and of falling precipitously, deliriously in love…In a blood-red restaurant (rather womb-like, if you ask me—a place in which a romantic obsession is born, surrounded by a bright red warning signs) Madeleine appears, walking through a doorway in a deep-green stole and pauses in profile like a mysterious work of art…In this manner Madeleine, and the color green, are introduced into Vertigo, and Scottie’s subconscious.

We get it, Hitchcock. Green is important. And now that I’ve covered the painfully obvious details, let’s move on. As Emerson mentions, this early scene in the restaurant introduces a new element: red. So what does all that red mean? Is it simply there to highlight the green of Madeleine’s dress? Or is it, as Emerson claims, a warning to Scottie? Well, this is where I part ways with Emerson. He is very quick to take the conventional, knee-jerk reactionary approach to an otherwise promising color analysis. If it’s red, it must be warning us, right? Red means DANGER, capital letters and all. Unfortunately, I don’t think that’s what the red in this particular film is about. It’s a good guess, but lacks the higher degree of critical thinking necessary when examining anything created by Hitchcock. “DANGER” would be a very simplistic message for an otherwise dizzyingly layered film. I feel that if Jim Emerson had managed to remember his color wheel, this problem would never have arisen. Don’t worry, I’ll explain.

Green and red are complementary colors. This means that they are opposite of each other on a color wheel. It also means that each highlights the other. (And when mixed, by the way, they produce a beautifully nondescript shade of dark gray.) So let’s follow this to its logical conclusion. I agree wholeheartedly that green represents Scottie’s fear, both of his vertigo and the same feeling induced by love. If red is the opposite of green, then it follows that red represents the opposite of this. Red signifies Scottie’s courage, occasionally counteracting his fear. However, his courage is just as frequently unfounded as his fear is. But that’s not the point. You cannot have red without the green. You cannot have courage without fear, and vice versa. The two are opposites, but part of each other, and Hitchcock is clearly playing with the same kind of duality seen throughout the film. Though green is almost never present without red nearby, this detail seems to have been overlooked–or at least trivialized–by most critics. It’s a shame, because I think this is one of the most important aspects of the film. Bear with me. I promise I’ll start to make sense soon. Prepare for an overwhelming (but necessary) deluge of screenshots. (Would you say I have a plethora?)

Let’s return to the RESTAURANT SCENE, briefly. The entire room is an intense red color, playing off of Madeleine’s green. She rises from her seat, displaying herself for Scottie, who is immediately captivated by her. Now here’s the really cool part. There is a reaction shot directly following his first few glimpses of her. And in this shot, Scottie’s normally blue eyes are green. Yes, green.

Intentional, Mr. Hitchcock! The color of his eyes in these few frames was clearly tampered with in post-production to achieve this effect. There is simply no other way they could have managed it. This must mean that Hitchcock thought it was a very important detail. I agree. The room is swimming in red and Scottie is confident. He’s just started this job and feels as if he can handle anything after his long break from police work. The red reflects these feelings of bravery and self confidence. Enter Madeleine. He sees her and is struck by something, but can’t really grasp what. She’s still far off, and red remains the dominant color. But when she moves closer, we see Scottie’s eyes light up with green. It is at this moment that he first experiences a flicker of doubt. She’s starting to affect him, and his courage wavers slightly.

I’m going to pause here to introduce (gasp) a new color. Everyone else seems to have ignored this, but I think it’s an important–even essential–supplement to the red and green. In my post earlier this week, I pondered the meaning of all the orange flowers. Well, now I’ve got it! Because green represents the fear associated with love and red represents the courage, orange has to play a similar, but separate role. Let me make this very clear–I don’t believe that orange is used in this movie as an occasional substitute for red. We need to assume that Hitchcock was extremely conscious of every color choice and every shot composition choice. So what does orange represent? Desire. Desire is related to the fear and courage that are associated with love and often intermingles with them, but is also separate. Hitchcock probably felt the need to differentiate between courage and desire. The courage goes hand-in-hand with the fear, whereas desire, represented by orange, is independent of these. Scottie is watching Madeleine in the graveyard, and we are suddenly presented with shots framed by orange flowers. Also note that it is not just Madeleine appearing with these orange flowers. Scottie has his own share of flaming flowery shots. When we realize that this whole scene is a very intentional act put on by Madeleine, we also realize that she must have been watching him. So for her, too, Scottie is surrounded by orange. Hmmm.

Moving on, we come to the FLOWER SHOP SCENE. Madeleine is standing right next to a stack of bright green boxes. That’s pretty clear. But wait! There are red flowers on her other side. Aha!

Hitchcock’s use of shots that cause the viewer to associate with the male lead, as discussed in Laura Mulvey’s FTC essay on page 845, is fairly consistent in this film.

Hitchcock’s use of shots that cause the viewer to associate with the male lead, as discussed in Laura Mulvey’s FTC essay on page 845, is fairly consistent in this film.

…use of subjective camera from the point of view of the male protagonist draw the spectators deeply into his position, making them share his uneasy gaze. The audience is absorbed into a voyeuristic situation within the screen scene and diegesis which parodies his own in the cinema…Vertigo focuses on the implications of the active/looking, passive/looked-at split in terms of sexual difference and the power of the male symbolic encapsulated in the hero.

Scottie is hiding behind a door, and the green boxes are the closest thing to him. He is clearly fearful, and in awe of Madeleine. But at the same time, those red flowers are present in the background, allowing him just enough courage to admire her from his hiding place. Though he’s lurking fearfully behind a door, Scottie is still being fairly bold in terms of the type and intensity of his attention towards Madeleine. Note also the continued presence of orange. Once again, Scottie is watching Madeleine, and enjoying it. There’s something very voyeuristic about these two scenes, although it could be argued that in both we’re not entirely sure who the true voyeur is. Madeleine is being intentionally exhibitionist, but she’s also watching Scottie carefully. And then there are these orange flowers all around them, perhaps symbolizing this mutual voyeuristic desire.

And now we arrive at the most important scene in the entire film, according to me. It is the OH MY GOODNESS, HE UNDRESSED HER AND NOW THEY’RE ALONE IN HIS APARTMENT scene. I will call it THE APARTMENT SCENE to save time. The first thing that we notice about this scene is that Madeleine is wearing a red robe and Scottie is wearing a green sweater. Have they reversed colors? Perhaps, but because these two colors are inseparable in terms of what they represent, it doesn’t particularly matter who is wearing what. Just as red and green are, when shown together, meant to be one entity, Scottie and Madeleine are one entity, unified by mutual attraction. Jim Emerson describes this scene:

After her “suicide attempt,” Madeleine reprises her initial entrance in Scottie’s apartment, coming toward him (and the camera) in a red robe that reminds us of the decor of Ernie’s restaurant in which we first spied her. On a table to the right of the frame is a striking green box (an ice bucket?) reminiscent of those at Madeleine’s florist —so green it’s somewhat distracting. The color scheme—red suggesting Scottie’s fear/caution/hesitancy when it comes to romance, and its opposite green, suggesting the Edenic bliss (and/or watery oblivion) of his infatuation with Madeleine (or, from Midge’s point of view, jealousy)—seems to be indicating perhaps that Madeleine may appear to be one thing, but may actually be another.

Emerson is pretty adamant about red representing caution and hesitancy, isn’t he? But in order to accommodate this, he’s changed his analysis of green. I don’t see why this is necessary. The problem he keeps running into is heavy reliance on the most common meanings associated with these colors in society. I feel very strongly that Hitchcock wouldn’t have been so simplistic as to use green to represent “Edenic bliss” or “jealousy”, just as he would not have had red represent “caution”. I have more faith in him than that. Let’s look at this critical scene shot-by-shot.

What is Scottie doing here at the beginning? Stoking the fire. The ORANGE fire, I might add. Got it? Also notice his green shirt, the green pillow, and the dull red window drapes.

Scottie is in green, obviously, but he’s also surrounded by green. The two pillows on either side of him and the green hue of the television screen create this effect. The only red in this shot is in the drapes, and it’s a very dull, subdued sort of red. Is Scottie’s fear, represented by green, overpowering his courage? Or is it perhaps simply that he is doesn’t feel the need for courage because he’s in his own apartment, in control of the situation. (He thinks.)

Well, this complicates things. The robe Madeleine is wearing is bright red and is, in fact, the only bright color we see, apart from a speck of green on the right. Suddenly the ratio has reversed. What is Hitchcock trying to say here about Scottie’s emotional state? Maybe in this scene Scottie is more comfortable with Madeleine than with the situation. He feels brave in respect to dealing with her, but a little fearful of the overall situation he finds himself in. After all, he undressed her, so perhaps he feels that he has a better knowledge and understanding of her. There’s nothing dangerous or mysterious about her, he’s telling himself. I’ve seen everything. But is Madeleine wearing the red for him or for herself? And what about Scottie’s green? Is his green sweater an open defiance of his former fear? That bright green pitcher in the corner seems to be reminding him to be careful. This is especially meaningful when considering that it’s side-by-side with Madeleine and her red. It’s saying that she’s not as safe as she looks. This also further complicates the voyeur/exhibitionist question. Is he the voyeur because he undressed her and enjoyed it, or is she the voyeur because, in a way, she had control of the situation and was using it as an exercise to observe something about him?

And of course, Madeleine sits right in front of bright orange flames.

Something that’s very important about this shot (which is a point-of-view shot from Scottie’s perspective) is the fact that Madeleine is in focus but the fire is not. So the desire is there, but he’s still focusing most of his attention on her. His guard is not quite down. The climax (ha) of this scene has not yet been reached.

Alas, when Scottie looks at her, he sees only red. There is no green for him at the moment. But don’t think that his is entirely due to his overconfidence. Madeleine has chosen to sit on the ground in front of the fire, rather than on the couch, between the green pillows. She is intentionally surrounding herself with red and, yes, orange. She’s encouraging his bravery and desire, but attempting to block fearful feelings that might cause him to behave with more caution.

And suddenly they’re in the same shot. Note that the green pillows that were on the couch at the start of the scene are no longer visible. The only green is Scottie’s sweater. His fear is gone. So this is when Madeleine decides to make her move.

Just look at this shot. Her expression in combination with the now in focus orange flames. She’s making herself completely available to Scottie, posing once again. The message is very clear: “I want you. I know you want me.” This shot is entirely about their mutual, burning desire.

And to some degree, they have acted upon their mutual desire. Look at the way in which green and red, the sole colors in this shot, are intertwined. And what do each of their expressions say? It looks like Scottie’s says “don’t worry”, while Madeleine’s expression is much more concerned and cautious. She’s trying to warn him, but he doesn’t notice because of the red. At the end of the scene, the red is all he’s left with. He is left alone with his overconfidence.

We move now to a very different location: Midge’s apartment. There has been quite a bit of discussion over the Midge/Madeleine question, especially in Ben’s blog. Despite the general consensus that Midge does not put herself on display the way Madeleine does, this is not entirely true. Midge does try to do this exactly the same way, though not consistently. So let’s look at what Midge chooses to surround herself with.

Ah, orange again. Her walls, furniture, and even the glow of the light are all orange. We see later that her shirt is actually red, but in this shot it definitely looks orange. Intentional, of course. In this scene, Midge is displaying herself for Scottie, probably because she thinks that’s what he wants. She even wears red in the same way that Madeleine does, an attempt at lowering his guard. As Mary Carolyn points out, Midge is willing to make many sacrifices for Scottie, including molding herself into what she thinks he wants.

Ah, orange again. Her walls, furniture, and even the glow of the light are all orange. We see later that her shirt is actually red, but in this shot it definitely looks orange. Intentional, of course. In this scene, Midge is displaying herself for Scottie, probably because she thinks that’s what he wants. She even wears red in the same way that Madeleine does, an attempt at lowering his guard. As Mary Carolyn points out, Midge is willing to make many sacrifices for Scottie, including molding herself into what she thinks he wants.

But what’s missing here? The green, of course. Midge cannot be Madeleine because she doesn’t have the green to counteract red. She is wearing red, the color of bravery, but it doesn’t do her much good. Perhaps because to create love you need both red and green, and she’s missing the green—it’s whatever Madeleine/Judy has that makes the romance complete. Emerson says that “Midge is wearing bright red when she attempts to put a stop to Scottie’s romantic illusions about Madeleine.” Again, I disagree. Midge is not wearing red for Scottie. She’s wearing it for herself, because she’s the one who needs the added courage. But how can she possibly succeed without the other aspect of love as represented in this film? Midge is doomed from the start. Let’s jump to a later scene involving Midge.

It’s true that she has the red and green, but there’s something a little off about the red. It’s not quite right. And the flowers are probably reminding Scottie of the graveyard scene with Madeleine. Midge is trying so hard, but things just aren’t right between them. It is unclear whether it’s because she is wrong, or because Scottie is so obsessed with Madeleine that he will never really see Midge.

Another vitally important scene is the one in which Scottie ‘discovers’ Judy. There was a little discussion of this in class, and the details definitely support the idea that Judy, once again, is conscious of Scottie’s focus on her and takes advantage of it. One remarkable thing about this scene is that it very clearly foreshadows her reappearance. Remember the green boxes that were beside Madeleine in the flower shop scene? Scroll up and take another look at them. Now, just before Scottie turns and glimpses Judy, a woman walks past him carrying one of these boxes. Coincidence? I think not.

Whoa. Now what about Judy? Not only is she wearing a green dress, but she is walking next to a woman in red. She then positions herself opposite the woman in red, once again emphasizing the thematic juxtaposition of these two colors. Since this scene follows the one with Midge, it reinforces the fact that Judy is the right one because she comes with both colors and Midge, sadly, does not.

Whoa. Now what about Judy? Not only is she wearing a green dress, but she is walking next to a woman in red. She then positions herself opposite the woman in red, once again emphasizing the thematic juxtaposition of these two colors. Since this scene follows the one with Midge, it reinforces the fact that Judy is the right one because she comes with both colors and Midge, sadly, does not.

This time, all Scottie sees is the green. But instead of letting the fear this represents guide his actions, he finds himself drawn by it. That’s a very dangerous situation. Because he associates his fear with Madeleine, he is anxious to move closer to it, even to embrace it, if it means recapturing what he’s lost. Judy, on the other hand, is completely conflicted. In a green dress, she’s moved to place herself once again on display for Scottie. She wants him to watch her, rediscover her, and renew their former relationship, but she’s also warning him off at the same time. By reminding him of his fear, she may assume that this will be enough to keep him safe. However, whether she realizes it or not, her prominent display of herself and the green of her dress has the opposite effect on him. And maybe she’s hoping, just a little, that it will. As she walks away, a man in an orange(ish) jacket approaches. Could this message be any clearer? At this point, how can Scottie resist following her?

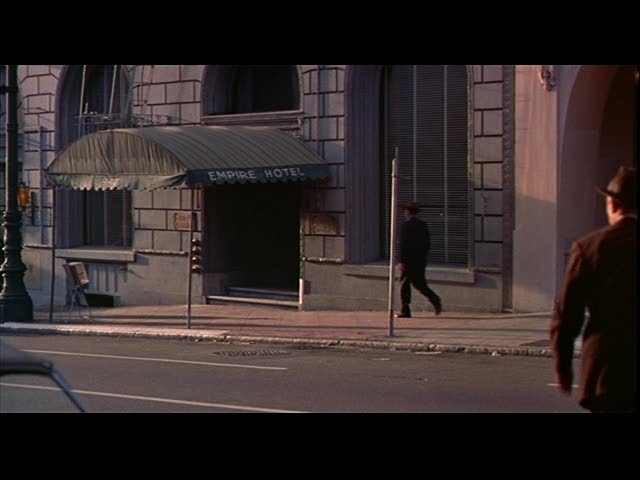

Let’s look at Judy’s hotel. The overhang is green, while the neon sign, unlit by day, is red.

According to interviews, Hitchcock chose the Empire Hotel specifically because their sign glows bright green at night. But did he also realize that it’s red during the daytime, or was that simply a lucky coincidence? Even the sign of Judy’s hotel supports the duality of color and emotion in the lives of the characters.

According to interviews, Hitchcock chose the Empire Hotel specifically because their sign glows bright green at night. But did he also realize that it’s red during the daytime, or was that simply a lucky coincidence? Even the sign of Judy’s hotel supports the duality of color and emotion in the lives of the characters. And look! Judy has a red wallet. This is what settles it for Scottie. She has the green and the red. As if he needed more reinforcement, take a look at these shots:

And look! Judy has a red wallet. This is what settles it for Scottie. She has the green and the red. As if he needed more reinforcement, take a look at these shots:

In a last attempt to warn Scottie off, Judy has positioned herself right in front of the green. We can’t even see the details of her face; green is all there is. But Scottie is so far beyond caring by this point that it accomplishes nothing. He probably notices the warning, the fear, but is so obsessed by now that he simply chooses to ignore its implications.

Scottie has had Judy dress in orange and green in this scene. The green reminds him of his fear, and thus of Madeleine, while the orange signifies his continuing desire. Notice also that there are minuscule amounts of red in this scene, but Scottie is not focused on them. He doesn’t need his courage anymore. There is no need for confidence when he has plunged so far into obsession.

Scottie has had Judy dress in orange and green in this scene. The green reminds him of his fear, and thus of Madeleine, while the orange signifies his continuing desire. Notice also that there are minuscule amounts of red in this scene, but Scottie is not focused on them. He doesn’t need his courage anymore. There is no need for confidence when he has plunged so far into obsession.

And finally, the scene that every critic and every film teacher seems to adore.

Once again, Scottie’s eyes are tinted green. He sees Madeleine for the first time…again.

Once again, Scottie’s eyes are tinted green. He sees Madeleine for the first time…again. Our buddy Jim Emerson discusses this.

Our buddy Jim Emerson discusses this.

From inside Judy’s room, the whole room is suffused with that green light, filtered through fine-mesh curtains. As Judy emerges from the bathroom, competing her visual transformation into Madeleine, she is bathed in green and shot through a hazy filter that recalls the soft, dreamy lighting of the garden sequence…As he kisses Judy/Madeleine, the camera circles dizzyingly—vertiginously, you might say—around them and the whole world bursts into green—green, the color of rebirth, of growth.

I’ll overlook the fact that he’s created yet another meaning for green because he has an excellent point. Although Scottie has been watching Judy and the green around her, even surrounding her with it intentionally, it is not until he is practically drowned in green–until they are drowned in it together–that he feels as if he’s truly rediscovered Madeleine and the emotions associated with her. They are both enveloped in fear, and Scottie finds this exhilarating. We’re not sure how Judy feels about this, but it seems pretty clear that she is not enjoying the feeling as much as he is.

Here, Scottie sits in a green chair, watching Judy enter the room. He has embraced his fear. He lives for it. He is beyond help. And then there’s the clincher.

It’s the final red. Her last attempt to balance out the frightening effects of the green. Does it work? Well, the ending can be argued either way. The final scene is mostly gray, which is, if you remember, the color you get when red and green are mixed. It is a culmination of their emotions, the ultimate result of the two sides of their love. It is also the final solution to Scottie’s obsession. This red, counteracting the green light, puts an end to everything. Problem solved, though not happily. But how could it be? When love is based only on fear, can there be a happy ending?

I’d like to explore the greater symbolic meanings of these colors a little further. I’m going to make a sweeping philosophical statement and assert that the interplay of courage and fear is essential to love. The euphoria commonly associated with romance is produced entirely by this balance. So is this what love is all about? Courage and fear? Perhaps. (And don’t forget the orange, the desire.) However, if these were the only necessary elements for love, wouldn’t things have worked out for Scottie and Judy? Or, perhaps, they weren’t destined to be together at all. This brings up the question of soul mates all over again. Does the fact that things don’t ultimately end well mean that it was never meant to be? Are Scottie and Judy, just like Eben and Jennie, doomed from the outset? Is their love less true because it doesn’t culminate in their lasting happiness? This question leads nicely into…

PART TWO:There has been quite a lot of discussion over what exactly distinguishes Midge from Madeleine, and what makes Madeleine ‘right’ for Scottie. However, this approach is inherently flawed, because it assumes that Madeleine is right for Scottie. In my post on the 13th, I said that

Eben and Jennie are not soul mates…Their love is not true. On Eben’s part, it’s the idea of it and on Jennie’s side…who knows? They’re both completely in love with the idea of love and the security and comfort of it.

What does Eben love about Jennie? She makes him feel wanted. She’s mysterious. She represents variation and excitement in the monotony and misery of his daily life. Does he really know her? I don’t think so.

And what does Jennie love about Eben? He’s her anchor. As she says, she’s lost, and he keeps her grounded.

I stick by this previous assessment. In fact, I think we can draw some meaningful parallels between these reasons for love and the reasons in Vertigo. Scottie is attracted to Madeleine for the same reasons that Eben is attracted to Jennie. Both women are glamorous, mysterious, and elusive. As for Judy’s attraction to Scottie, I think she and Midge aren’t actually as dissimilar as we first thought. They both seem to need their respective men, for whatever reasons. Jennie feels lost, and clings to Eben for this reason. Perhaps Judy also feels lost. A huge part of her identity was destroyed in the first half of the movie, as it is fairly clear that she has trouble separating herself from Madeleine. They’re two aspects of the same person, and so perhaps the only thing that makes Judy feel as if she hasn’t lost that part of herself is being with the person who knew them both. This is, of course, Scottie. Steph’s discussion of Judy’s split identity as well as her general discussion of duality in Hitchcock films is particularly relevant.

But regardless of their motivations for entering into it, why does their relationship fail ultimately?

Should we put all the blame on Scottie because, as Craig says, he has “descended deeper into a focused obsession, becoming less and less patient with someone he claims to love”? We could easily ask the same question of Eben and Jennie. Does Eben’s obsession with the idea of Jennie limit the extent to which they can take their relationship, and ultimately lead to their downfall? But Madeleine also plays an active role in encouraging Scottie’s obsession, just as Jennie encourages Eben’s attachment to her for fear of losing him or herself. I think both women have the same basic motivation.

Stephanie H. proposes the opposite of Craig, deciding that Judy is

the shadow of the ideal female. She is the one that is dangerous, intriguing and sexual. She uses those qualities to seduce Scottie into “following” her and she eventually gets him to fall in love with her. She lies to him and deceives him and is ultimately responsible for his downfall as well as her own.

If we extend this idea back to Portrait of Jennie, isn’t it similarly possible that Jennie’s selfishness in needing someone to cling to leads to eventual misery for both of them? Or is the problem perhaps in the transitory nature of both women? Leighton makes a good point when she questions the reality that both Eben and Scottie are creating for themselves. “Both are trying to create a woman who, arguably, does not exist.” Although stated very simply and without extensive further discussion, this is a brilliant assessment and summary of both films. I feel that Leighton encapsulated the main relationship between the two films perfectly.

Another issue worth exploring is that of timing. The idea was explored in class that Eben and Jennie are soul mates whose lives just didn’t happen to coincide, so time ‘bent itself’ to accommodate them. Megs has a great commentary on this idea of time being an inhibiting factor in a relationship, but ultimately working out if the love is ‘true’.

I don’t think we’ll ever answer this question of ‘true love’ and ‘soul mates’. But would we really want to? If love is something that can be explained, then doesn’t it lose a bit of its appeal? I would argue that the thing that makes any theory like this so tantalizing is, in fact, its ambiguity. Like Scottie and Eben, we like to pursue things we don’t understand. After all, the questions, at least in this case, are much more important than the answers.