TWELVE ANGRY MEN… from a different perspective.

This is an assignment for my small group communication course, so I’ll be examining this film (which happens to be one of my all-time favorites) for its group problem-solving elements. Fun!

–

Lesson One: The flaws of having appointed leaders

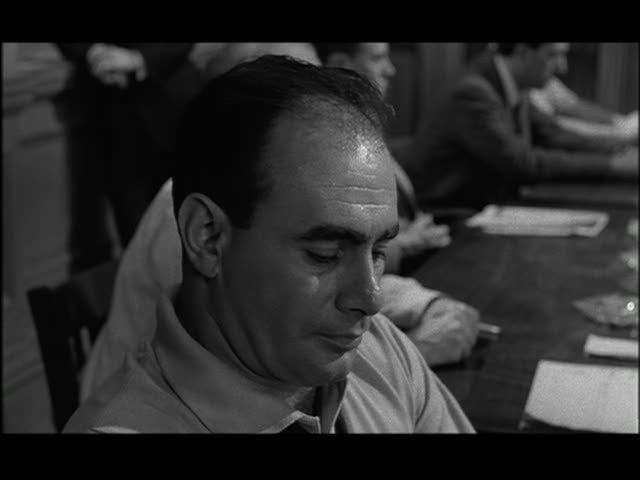

The most immediately apparent lesson involving functional (or, in this case, dysfunctional) small group decision making is the question of leadership and evolving roles of group members. Though there were many factors that contributed to the conflict of the jury members, one of the main complications was the fact that there was no distinct leader. This might have been all right if each member had respect for the others and their opinions, but in this case the leadership role was necessary for group progress. It is clear very early on in the film that the appointed leader, the foreman (Jury Member 1), is a little insecure with the role given him and lacks the assertiveness to maintain order in a group of this size and diversity. Even a simple exchange in the opening stages seems to make him uncomfortable with his status:

Jury member: “Should we sit in order?”

Foreman: “Gee, I dunno…I guess so.”

Even though the question isn’t a particularly important one, the way he handles it and later tries to enforce it reveals how little confidence he has in his ability to maintain this position and comfort with it. He’s fairly timid and consistently has difficulty getting the attention and cooperation of the other jury members. It seems as if he’d be much better–and happier– with an organizational role rather than a leadership one. He begins by offering different options for how to proceed with the discussion, but the reaction shots of the other members show that he’s not really viewed as a particularly authoritative figure. The type of initial vote that he decides upon is also not the best way of making everyone’s opinion heard. While preliminary voting is useful when determining very generally where the group stands, it’s important to remember that it is meant to be a starting point for discussion, not a decision in itself. When the other jury members are unhappy about the lone dissenting vote, he fails (yet again) to maintain proper control when everyone jumps on Henry Fonda’s character and it takes the group a significant amount of time to take the next step into discussion.

Later he tries to enforce the decision of going around in a circle and letting everyone have a chance to speak, but he seems uncomfortable even asserting his own power: “Wait a minute. We, uh, decided to do this a certain way and I think we oughta stick to that way.”

The way this is going for him, it is practically inevitable that someone will challenge his authority, and a conflict arises over this. Annoyed, he says, ““You think it’s easy? You take over” and sits, facing away from the group and visibly upset. When another member asks him for his approval of a step being taken in the discussion, his only response is: “I don’t care what you do.”

This continues, and in this way his role gradually shifts further away from a leadership one and more towards that of a moderator and coordinator, while Jury Member 8 (Henry Fonda) moves closer to being the leader. The bottom line is that the best way to establish a group leader is to simply let one emerge naturally. This is also true for each of the other group roles, and several very clearly developed roles become apparent as the film continues.

—

Lesson Two: Approaching the discussion with an open mind

The idea of being an unbiased group member is a pretty straightforward one, but something that many groups tend to forget, at least initially. The characters in the movie are fairly extreme examples of this, but it’s important to remember that even in a group that seems homogeneous, each person is always going to have a slightly different perspective. It’s completely fine to let this affect the way you approach the discussion and feel about the subject matter, but it’s quite another matter when personal prejudices interfere with the group’s progress and put a strain on relations between group members. Two jury members (3 and 10) illustrate this particularly well. Between them, they represent two different kinds of biases that can be found in a group like this. Through his speech about the unsatisfactory moral character of all residents of slums, Jury Member 10 reveals exactly how prejudiced he is. Not only does this impede discussion by creating intense conflict, but it creates feelings of antagonism between him and other members of the group, which is not at all conducive to the kind of teamwork they’re attempting to accomplish. Jury Member 3 has a personal agenda. He is upset about his own son, as he explains at the beginning, and this emotional anxiety he’s feeling leads to a desire to take out his hurt feelings on someone who is wholly unconnected with his real problem–the defendant. For him, it’s a personal vendetta, and the other group members have a hard time understanding and tolerating the behavior that results from this.

He is the last, and most difficult to convince because his reasons for wanting to convict are based on emotion rather than logic. Although these characters are extreme, they serve as good representations of common mistakes groups can fall into. Everyone has biases, but when an objective decision is called for, remaining as unbiased as possible is vitally important. Members of a group like this should examine both their own motives and also take into consideration where each other group member is coming from. Mutual understanding and respect is something that most groups take for granted until it is thrown into question.

–

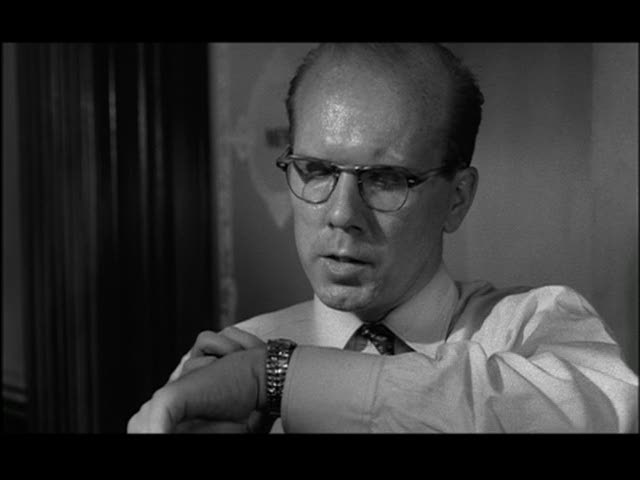

Lesson Three: Appealing to different learning styles

Henry Fonda’s character (Jury Member 8) is remarkably persuasive. Is this just because he’s a good leader? Is it because he’s unquestionably right? Or is it, perhaps, his tactical approach to the task of convincing his fellow group members? Unless all members of a group come from identical backgrounds and hold the exact same opinions and beliefs on everything, people are going to disagree. One of the most important steps of group problem solving is discussion, of which persuasion is an integral part. What exactly is it that Henry Fonda is doing from the point he casts the lone dissenting vote to the end of the film, when everyone is (at last) in agreement? He convinces all 11 of his group members, some of whom were vehemently opposed to his opinion, to change their votes. And the cool part is, he does it by employing a technique most of us (especially teachers) are very familiar with. He appeals to different learning styles. His three main arguments are each geared towards a different type of learner.

The first argument is the one involving the knife. By actually producing a knife identical to the one belonging to the defendant, he makes a very visual appeal to his group members. They can see the two knives side-by-side, and are forced to accept the possibility, however slight, that the boy’s father could have been killed with another knife.

The second, the question of the train, appeals to more auditory learners, which is appropriate considering the auditory nature of that specific piece of evidence. He outlines clearly and logically the timing of the train and amount of sound it would produce. This is done in such a way that the other jury members can follow his arguments to their logical conclusion, one that they eventually accept as true.

The third piece of persuasion is the one involving the timing of the witness getting out of bed and running to the door. He appeals to kinesthetic learners by actually getting up and demonstrating the chain of events, even letting another group member time him. This exercise maintains interest through its interactive nature and is also a highly effective technique.

Throughout his main arguments, he continually appeals to jury members for input, drawing on their personal experience and opinions. This also strengthens his arguments because they’re composed of elements contributed by other group members. Good persuasive ability is essential during discussions, and he manages to overcome extreme differences in the group through these tactics.

I think I’ve watched this film 4 or 5 times, but this is the first time I’ve noticed many things, probably because I’m approaching it from the perspective of a small group analyst rather than that of a film student. It’s interesting to be paying attention to possible group roles and organizational difficulties rather than camera angles and filmmaking techniques. But perhaps the complications of group interaction and their accurate portrayal is just as important to consider as all the other elements of film. This just reinforces the idea that film is incredibly versatile and multidimensional. I can’t wait to see what I’ll discover next.